INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON

OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

I am confident that SP Guide Publications would continue to inform, inspire and influence.

My compliments to SP Guide Publications for informative and credible reportage on contemporary aerospace issues over the past six decades.

- Interim Defence Budget 2024-25 — An Analysis

- Union Defence budget 2024

- Indian Army: In quest of greater firepower and policy recommendations for gaps

- Indian Army Annual Press Conference 2024

- 6G will transform military-industrial applications

- Tata Boeing Aerospace Delivers 250 AH-64 Apache Fuselages, Manufactured in India

Reforms in Managing National Security

India’s national security continues to be sub-optimally managed. Strategic reviews need to be undertaken periodically to evolve a comprehensive national security strategy.

India at present faces complex external and internal security threats while new challenges are emerging on the horizon. Unresolved territorial disputes with China and Pakistan, insurgencies in Jammu and Kashmir and the North-eastern states, the rising tide of leftwing extremism (LWE) and the growing spectre of urban terrorism, have vitiated India’s security environment and slowed down socio-economic growth. Yet, as the recent serial blasts at Mumbai have once again indicated, India’s national security continues to be sub-optimally managed. Strategic reviews need to be undertaken periodically to evolve a comprehensive national security strategy

In 1999, the Kargil Review Committee, headed by late K. Subrahmanyam had been asked to “review the events leading to the Pakistani aggression in the Kargil District of Ladakh in Jammu & Kashmir; and to recommend measures as are considered necessary to safeguard national security against such armed intrusions”. Though it had been given a very narrow and limited charter, the committee looked holistically at the threats and challenges and examined the loopholes in the management of national security. The committee was of the view that the “political, bureaucratic, military and intelligence establishments appear to have developed a vested interest in the status quo’’. It made farreaching recommendations on the development of India’s nuclear deterrence, higher defence organisations, intelligence reforms, border management, the defence budget, the use of air power, counter-insurgency operations, integrated manpower policy, defence research and development, and media relations. The committee’s report was tabled in the Parliament on February 23, 2000.

The Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) appointed a Group of Ministers (GoM) to study the Kargil Review Committee report and recommend measures for implementation. The GoM was headed by Home Minister L.K. Advani and four task forces were set up on intelligence reforms, internal security, border management and defence management to undertake in depth analysis of various facets of management of national security.

The GoM recommended sweeping reforms to the existing national security management system. On May 11, 2001, the CCS accepted all its recommendations, including one for the establishment of the post of the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), which has still not been implemented. A tri-Service Andaman and Nicobar Command and a Strategic Forces Command were established. Other salient measures included the establishment of HQ Integrated Defence Staff (IDS); the Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA); the establishment of a Defence Acquisition Council (DAC), headed by the Defence Minister with two wings—the Defence Procurement Board and the Defence Technology Board—and the setting up of the National Technical Research Organisation (NTRO). The CCS also issued a directive that India’s borders with different countries be managed by a single agency—“one border, one force”—and nominated the CRPF as India’s primary force for counter-insurgency operations.

Ten years later, many lacunae still remain in the management of national security. The lack of inter-ministerial and inter-departmental coordination on issues like border management and Centre-state disagreements over the handling of internal security are particularly alarming. In order to review the progress of implementation of the proposals approved by the CCS in 2001, the government appointed a Task Force on National Security led by former Cabinet Secretary Naresh Chandra. The task force has submitted its report.

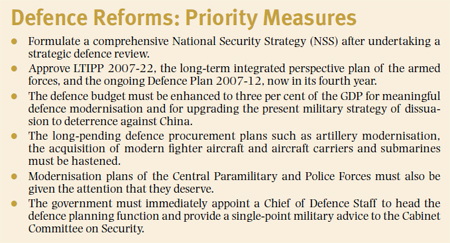

The first and foremost requirement for improving the management of national security is for the government to formulate a comprehensive National Security Strategy (NSS), including internal security. The NSS should be formulated after carrying out an inter-departmental, inter-agency, multidisciplinary strategic defence review. Such a review must take the public into confidence and not be conducted behind closed doors. Like in most other democracies, the NSS should be signed by the Prime Minister, who is the head of the government, and must be placed on the table of Parliament and released as a public document. Only then will various stakeholders be compelled to take ownership of the strategy and work unitedly to achieve its aims and objectives.

It has clearly emerged that China poses the most potent military threat to India and given the nuclear, missile and military hardware nexus between China and Pakistan, future conventional conflict in South Asia will be a two-front war. Therefore, India’s military strategy of dissuasion against China must be gradually upgraded to deterrence. Genuine deterrence comes only from the capability to launch and sustain major offensive operations into the adversary’s territory. India needs to raise new divisions to carry the next war deep into Tibet. Since manoeuvre is not possible due to the restrictions imposed by the difficult mountainous terrain, firepower capabilities need to be enhanced by an order of magnitude, especially in terms of precision-guided munitions. This will involve substantial upgradation of ground-based (artillery guns, rockets and missiles) and aerially-delivered (fighter-bomber aircraft and attack helicopter) firepower. Only then will it be possible to achieve future military objectives.

Consequent to the leakage of the Chief’s letter and the major uproar in Parliament that followed, the Defence Minister is reported to have approved the Twelfth Defence Plan 2012-17 and the long-term integrated perspective plan (LTIPP) 2012-27, in early April 2012. While this is undoubtedly commendable, it remains to be seen whether the Finance Ministry and subsequently the CCS, will also show the same alacrity in according the approvals necessary to give practical effect to these plans. Without these essential approvals, defence procurement is being undertaken through ad hoc annual procurement plans, rather than being based on carefully prioritised long-term plans that are designed to systematically enhance India’s combat potential. These are serious lacunae as effective defence planning cannot be undertaken in a policy void.

The government must commit itself to supporting long-term defence plans or else defence modernisation will continue to lag and the present quantitative military gap with China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will become a qualitative gap as well in 10 to 15 years. This can be done only by making the dormant National Security Council a proactive policy formulation body for long-term national security planning. It may be noted that CCS deals with current and near-term threats and challenges and reacts to emergent situations.

The defence procurement decision-making process must be speeded up. The Army is still not having towed and self-propelled 155mm howitzers for the plains and the mountains and needs to acquire weapons and equipment for counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations urgently. The Navy has been waiting for the INS Vikramaditya (Admiral Gorshkov) aircraft carrier for long and which is being refurbished in a Russian shipyard at exorbitant cost. Construction of the indigenous air defence ship is also lagging behind.

The plans of the Air Force to acquire 126 multi-mission, medium-range combat aircraft in order to maintain its edge over the regional air forces are also stuck in the procurement quagmire. All the three Services need a large number of light helicopters. India’s nuclear forces require the Agni-III missile and nuclear-powered submarines with suitable ballistic missiles to acquire genuine deterrent capability. The armed forces do not have a truly integrated command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, information, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4I2SR) system suitable for modern network-centric warfare, which will allow them to optimise their individual capabilities.

All of these high-priority acquisitions will require extensive budgetary support. With the defence budget languishing at less than two per cent of India’s GDP—compared with China’s 3.5 per cent and Pakistan’s 4.5 per cent plus US military aid—it will not be possible for the armed forces to undertake any meaningful modernisation in the foreseeable future. Leave aside genuine military modernisation that will substantially enhance combat capabilities, the funds available on the capital account at present are inadequate to suffice even for the replacement of obsolete weapons systems and equipment that are still in service, well beyond their useful life cycles. The Central Police and Paramilitary Forces (CPMFs) also need to be modernised as these are facing increasingly more potent threats while still being equipped with obsolescent weapons.

The government must also immediately appoint a Chief of Defence Staff or a permanent Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, as recommended by the Naresh Chandra Committee on defence reforms, to provide single-point advice to the CCS on military matters. Any further delay in this key structural reform in higher defence management on the grounds of the lack of political consensus and the inability of the armed forces to agree on the issue, will be extremely detrimental to India’s interests in the light of the dangerous developments taking place in India’s neighbourhood. The logical next step would be to constitute tri-Service integrated theatre commands to synergise the capabilities and the combat potential of individual services. It is time to set up a Tri-Service Aerospace and Cyber Command to meet the emerging challenges in these fields. International experience shows that such reform has to be imposed from the top down and can never work if the government keeps waiting for it to come about from the bottom up.

The defence budget has dipped below two per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) despite the fact that the services have repeatedly recommended that it should be raised to at least three per cent of the GDP, if India is to build the defence capabilities that it will need to face the emerging threats and challenges and discharge its growing responsibilities as a regional power in South Asia. The government will do well to appoint a National Security Commission to take stock of the lack of preparedness of the country’s armed forces and to make pragmatic recommendations to redress the visible inadequacies that might lead to yet another military debacle.

The writer is a former Director, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi. The views expressed by the author are personal.