INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON

OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

I am confident that SP Guide Publications would continue to inform, inspire and influence.

My compliments to SP Guide Publications for informative and credible reportage on contemporary aerospace issues over the past six decades.

- Interim Defence Budget 2024-25 — An Analysis

- Union Defence budget 2024

- Indian Army: In quest of greater firepower and policy recommendations for gaps

- Indian Army Annual Press Conference 2024

- 6G will transform military-industrial applications

- Tata Boeing Aerospace Delivers 250 AH-64 Apache Fuselages, Manufactured in India

Lessons Learnt and the Way Forward

India’s national security framework and its antiquated civil-military relationship have not grown in step with the needs of new security challenges. We need to change our mindsets and attitudes and look beyond the narrow boundaries defined by turf and parochialism.

“Relations between great powers cannot be sustained by inertia, commerce or mere sentiments.”

—Aaron Freidburg in New Republic, August 4, 2011

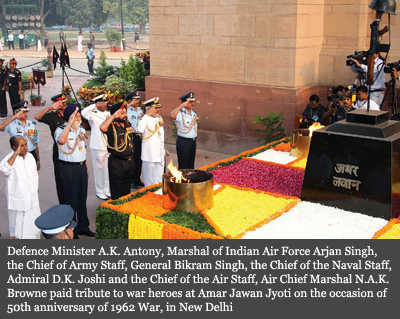

The India-China war in 1962 was independent India’s most traumatic and worst ever security failure which left an indelible impression on our history and psyche. This October marks its 50th anniversary: an appropriate occasion to reflect on its strategic lessons and our current politicomilitary status vis-à-vis China.

Background

It all started with China’s occupation of Tibet, and their surreptitious construction of a strategic road through Aksai Chin, joining Tibet with Sinkiang. The Government of India took two-and-a-half years to confirm the road construction and another one year to disclose it to the Parliament on August 31, 1959.

The uprising in Tibet caused further worsening of relations. In March 1959, the Dalai Lama fled from Tibet and took shelter in India. China suspected that India was helping the Khampa rebellion and had enabled Dalai Lama’s escape to India. This, alongside skirmishes on several border posts, resulted in the hardening of attitudes. India adopted a strategically flawed ‘forward policy’ of erecting isolated check posts without taking any measures to improve border infrastructure or the armed forces’ capabilities. Failure of the government policy put Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru under intense domestic pressure. He ordered the military to throw out the Chinese from intruded Indian Territory–a task that was well beyond its capability.

In October 1962, the Chinese military launched pre-meditated and calibrated punitive attacks in India’s northwest and northeast sectors of Ladakh and North-East Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh). India suffered its worst ever military defeat, and a geographic surgery that continues to fester in the form of line of actual control (LAC) till date.

There are many lessons. My emphasis is on strategic thinking and planning, civil-military relations and capability-building to tackle potential security threats.

Grand Strategy

According to a Pentagon historical study paper on the Sino-India Border Dispute, de-classified in 2007, “Developments between late 1950 and late 1959 were marked by Chinese military superiority, which, combined with cunning and diplomatic deceit, contributed to New Delhi’s reluctance to change its policy toward the Beijing regime for nine years.”

The study records that the Chinese diplomatic effort was a five-year masterpiece of guile, planned and executed in a large part by Chou En-lai. The Chinese Premier deceived Nehru several times about Chinese maps and carefully concealed Beijing’s long-range intentions. He played on ‘Nehru’s Asian, antiimperialist mental attitude, his proclivity to temporise, and his sincere desire for an amicable Sino-Indian relationship’ and strung along Nehru by creating an impression through equivocal language that (a) it was a minor border dispute, (b) Beijing would accept the McMahon Line, and that (c) old Kuomintang period Chinese maps would soon be revised.

The Pentagon study claims that the Chinese and even Nehru saw the use of diplomatic channels as the safest way to exclude the Indian public, press, and Parliament. They used these channels effectively for several years till it became a military fait accompli for India due to the Chinese forces exercising actual control of the area. The study concludes that “in the context of the immediate situation on the border where Chinese troops had occupied the Aksai Plain in Ladakh, this was not an answer but rather an implicit affirmation that India did not have the military capability to dislodge the Chinese”.

Many researchers have pointed out that the then raging Sino-Soviet ideological war played a role in the Chinese decision-making, leading to the Sino-Indian 1962 war. Chinese leaders were also concerned that the US might use a Sino-Indian war situation to unleash Taiwan against the mainland. They used diplomatic subterfuge to obtain reassurance on both these fronts before the war.

India’s Security Policy During this Period?

It is evident that despite Sardar Patel’s prophetic advice to Nehru on Tibet, China and Indian security issues on November 7, 1950 (contents of this letter were kept secret for 18 years), the Indian Government showed no strategic foresight or planning. When Chinese forces reached Changtu on their way to Lhasa, the Indian delegation in the United Nations blocked consideration of a proposal to censure China. In December 1950, Nehru publically supported the Chinese position on the grounds that Tibet should be handled only by the parties concerned i.e. Beijing and Lhasa. The government even allowed Chinese food material to go through Calcutta and Gangtok to reach Chinese troops in Yatung. In September 1952, India agreed with Chinese authorities to withdraw its military-cum-diplomatic mission in Tibet.

In the decade preceding 1962, the Indian ruling elite was convinced that having woven China into the Panchsheel Agreement, it had managed to craft a sound ‘China policy’. It was neither alert to the Chinese military developments in Tibet nor to the construction of Sinkiang-Tibet road which began in March 1956. Even after 1959, when China displayed its aggressive designs, Indian leaders were profoundly affected by the remoteness and difficulties of Aksai Chin and Tibetan terrain, forgetting that Zorawar Singh, Macdonald and Colonel Younghusband had led Indian troops to these very areas for strategic reasons in the past. Primarily due to ideological and emotional reasons, the Chinese geostrategic challenges and threats were either not accepted or underplayed till the Parliament and public opinion forced the government to adopt a military posture against China for which it was never prepared.

Military Strategy

Towards the end of 1961, Mao convened a meeting of China’s Central Military Commission and took personal charge of the ‘struggle with India’. Mao asserted that the objective was not a local victory but to inflict a defeat so that India might be ‘knocked back to the negotiating table’. By early September 1962, China started warning that if India ‘played with fire’; it would be ‘consumed by fire’. On September 8, 1962, 800 Chinese soldiers surrounded the Indian post at Dhola. Neither side opened fire for 12 days. The dice was cast for a showdown. The Chinese had conveyed their intention but we still thought that they were bluffing.

On October 6, 1962, Mao issued a directive to his Chief of Staff Lou Ruiquing, laying down the broad strategy for the projected offensive. The main assault was to be in the eastern sector but forces in the western sector would ‘coordinate’ with the eastern sector. The Chinese Military Command appreciated that the Indian Army’s main defences lay at Se La and Bomdi La. The concept of operations was to advance along different routes, encircle these two positions and then reduce them. Marshal Liu Bocheng outlined the military strategy of concerted attacks by converging columns. Indian positions were split into numerous segments and then destroyed piecemeal. The speed and ferocity of the attacks unhinged the Indian defences and pulverised the Indian command, resulting in panic and often contradictory decisions. Politico-military decision not to use combat air power was an unforgivable error of judgement.

Deception and surprise are enduring elements in the Chinese military strategy and Sino Indian 1962 war was a classic example. The Indian debacle was primarily the result of a failure of India’s strategic foresight and military capabilities.

Beijing justified the invasion as a “defensive act”. It must be noted that China, involved in the largest number of military conflicts in Asia, has always carried out military pre-emption in the name of strategically “defensive act” with no forewarning—Tibet invasion, entry into Korean War, 1962 conflict with India, border conflict with the Soviet Union in 1969, and attack on Vietnam in 1979.

Strategic Thinking

In his book, On China, Henry Kissinger treats the India-China border war of 1962 as an important illustration of the Chinese statecraft wherein “deterrent coexistence” and “offensive-deterrence”, defined as “luring in the opponents and then dealing them a sharp and stunning blow”, are important components. According to him, the confrontation triggered the familiar Chinese style of dealing with strategic decisions “thorough analysis; careful preparation; attention to psychological and political factors; quest for surprise and rapid conclusion”. He emphasises on the difference between the Chinese “comprehensive approach” to “segmented policy-making” by other nations. Kissinger concludes that behind the façade of “principled” ideological firmness/political toughness/historic civilisational patience, the Chinese leadership is capable of extreme elasticity and pliability, as seen in the physical contortions of a Chinese circus gymnast. Two other important lessons that emerge from this episode are: political realism versus ideological wish thinking, and interlacing of grand and military strategy.