INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON

OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

I am confident that SP Guide Publications would continue to inform, inspire and influence.

My compliments to SP Guide Publications for informative and credible reportage on contemporary aerospace issues over the past six decades.

- Interim Defence Budget 2024-25 — An Analysis

- Union Defence budget 2024

- Indian Army: In quest of greater firepower and policy recommendations for gaps

- Indian Army Annual Press Conference 2024

- 6G will transform military-industrial applications

- Tata Boeing Aerospace Delivers 250 AH-64 Apache Fuselages, Manufactured in India

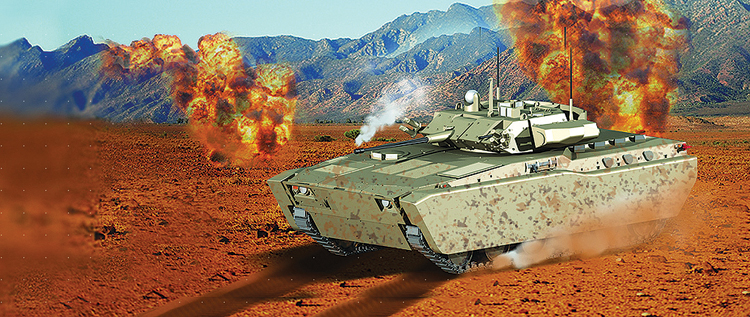

Future Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) Needs a De Novo Look

FICV, a key spearhead of the restructured Integrated Battle Groups, cannot be put in a limbo and such a critical capability programme must be classified as project of ‘National Strategic Security Importance”, for its national security sensitivity and multi spectrum operational capability and to address the future operational requirements and envisaged force profile with a de novo concept, design and technologies.

The Elusive Capability

FICV is yet another case history of selfinflicted injury, creating a capability gap with no effort to seek its accountability and responsibility. The Make 1 project seems to be a snakes and ladder game with more snakes than ladders, so the FICV is likely to be back at the starter block of discussion stage, that it was in 2004. Thus, FICV remains an illusion marred by frequent changes in procedural stance, bureaucratic apathy, cold feet for honouring promised financial support inspite of an AoN (October 2009) and disregard for the last EoI of July 2015 immaculately evaluated and sent to Ministry of Defence (MoD) in November 2016. Termed as a game changer and the biggest catalyst for an indigenous Integrated Defence Eco System and Defence Industrial Base, it has failed as a test case for ‘Make in India’, creating a glaring gap between expectations and outcomes. Resultantly, it has created disillusion in the nascent, yet vibrant indigenous private defence industry. A detailed analysis of the quagmire and way forward was penned in the article appeared in SP’s Land Forces 5/2018 on page number 1. Its time now to find a way ahead with a de novo look in the light of all options of Make1/Make2/SP not making a headway. Given our fragile security matrix, intentions can change fast, but capability building takes time. Thus FICV, a key spearhead of the restructured Integrated Battle Groups, cannot be put in a limbo and the impasse needs a fresh resolution.

Global Fire Power Index and Armoured Fighting Vehicle Ranking

2019 Global Fire Power Index recently unrevealed, rates India 4th (after USA, Russia and China) among 137 nations based on 55 individual factors. The criteria used in the rankings to determine military strength, included natural resources, local industry, geographical features and available manpower, besides military capability in each of the military specific sector. What is revealing is in some hidden analysis. While China stood third in the overall ranking, it was second in Armoured Fighting Vehicle (AFV) Sector, which primarily includes ICV and APC’s, while India was overall 4th, it ranks 25th in the AFV sector and Pakistan overall 15th ranked 19th in the AFV sector. Thus, not only has India slipped 21 ranks in AFV sector as compared to its overall standing, it ranks below Pakistan and the gap with China has widened. While it may be argued that numbers can be manipulated but we cannot adopt an ostrich approach to this widening capability gap by the FICV quagmire. Further, in the Global Armoured Vehicles Market Report, Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) market is estimated to register a CAGR of nearly 6 per cent during the forecast period of 2018 to 2023. Asia-Pacific is projected to be the fastest-growing regional market during the review period. This growth was attributed to the procurement and indigenous development of these vehicles in countries such as China, and India (FICV). However with FICV been put in a loop, the market trend will need to be reviewed impacting not only the indigenous defence industry but also induction of advance technologies in defence sector. Internally we need to introspect the foundational need to energise ‘Make in India’ in the defence sector, which in turn could resuscitate the FICV.

Energising Make in India – A Driver for FICV

As a self-respecting nation with increasing recognition in regional and global world order, India can ill afford to be dependent on imported weaponry. ‘Make in India’ is not just a sound economic option but a strategic imperative in promoting India as global hub of manufacturing, particularly in the strategic sectors such as defence. As of now the domestic defence industry lacks critical technologies, manufacturing ecosystems for integration of large platforms, supply chain and logistics. Ironically, India is the largest arms importer, accounting for close to 15 per cent of the global arms trade. No Indian defence manufacturing company figures in the top 30 global companies. The closest is the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) ranked 35th and Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) ranked 59th. This gap and balance between military might, growing economic resilience and a nascent defence industrial base needs to be addressed for national security and strategic autonomy.

The driver for a vibrant ‘Make in India’ will be the presence of a robust ecosystem, energised and driven by the industry friendly policies, time stipulated outcomes, with clearly defined accountability

The recent defence policy reforms and speeding up of acquisition process as part of ‘Make in India’ strategy, are most commendable but have commensurately not paid off in terms of their potential and outcomes. There exists a gap between expectations and deliverance due to a myriad of reasons including budgetary constraints, lacklustre implementation of policies, pervasive technological backwardness, delayed implementation of projects, skewed offset policies and evasive foreign direct investment (FDI), among other issues. The driver for a vibrant ‘Make in India’ will be the presence of a robust ecosystem, energised and driven by the industry friendly policies, time stipulated outcomes, with clearly defined accountability. Greater focus is also required on an innovative and collaborative ecosystem that includes academia, corporate and governmental partners, with user as the primary driver. Such a vibrant, interlocking ecosystem of diverse collaborators will prove to be a nurturing environment for the intense creativity in defence technology. ‘Make in India’ is also dependent upon indigenous R&D in military technology induction, manufacturing and product-technology & engineering, hence the need to focus on industry-driven R&D. In China nearly 25 per cent of the staff is deployed for R&D. Indian businesses deploy less than 10 per cent. We also need to constitute an Indian equivalent DARPA agency as in USA, to identify current or future advances that have the potential to bend today’s security trajectories with transformational and disruptive technologies. The focus must be on creating an environment that makes Indian firms to be world competitive and where all enterprises can flourish. ‘Make in India’ is indeed the enlightened strategic path which requires hand holding, patience, resilience and energisation by all stake holders. It may well have to traverse the transitory path of ‘Make for India’ (Buy and Make), Design for India and finally reach its true destination of an Indigenously Designed, Developed and Manufactured (IDDM) capability. Indeed, ‘Make in India’ must drive the enlightened path for FICV. Thus FICV programme in turn merits an apex level review, to arrive at alternate approaches for its revival.

Alternate Approach 1: De Novo Model

The first and foremost critical aspect for progressing FICV is to have a demonstrated intent at the apex level, to develop the capability by all stake holders. Second, the intent must be matched by an assured budgetary support based on benchmarks achieved and spread over the development cycle. Third, a de novo look is only required if there is no scope to carry forward the last EoI based on Make 1 of DPP 2016. Keeping in mind the national objective of self-reliance and focus on ‘Make in India’, the options of ‘Buy and Make’, ‘Buy Global’ or ‘G to G’, can only be a fall back option should all other avenues fail. Therefore, the design and development of FICV has to done in India.

Such a critical capability programme must thus be classified as project of ‘National Strategic Security Importance”, for its national security sensitivity and multi spectrum operational capability. It will also lead to an infusion of critical and emerging technologies for which we are presently import dependent. The need of the hour, therefore, is to look at a de novo approach, which will be based on collaborative convergence and a “Risk Sharing – Gain Sharing” formula. It also must not necessarily be restrained by the DPP, and achieve the design and development process at the desired pace.

The first criteria is to demystify the developmental approach of FICV, based on an evolutionary or revolutionary approach. While the evolutionary approach will be based on essentially an upgrade plus capability, the final product will be a modernised version of the existing BMP-2 within its design constrains. Thus, not the best option for a long term solution for FICV and at best can be an interim solution to bridge the existing capability gap with upgradation of BMP-2. The revolutionary approach as opposed to above is ordained to address the future operational requirements and envisaged force profile with a de novo concept, design and technologies. Again, the option under revolutionary approach is either to have a ‘Greenfield’ option or a ‘Hybrid’ option. However, pragmatism demands that the development be based on the Hybrid option, where in the programme is user-driven, involving leading AFV design agencies of the world, duly incorporating the experience and expertise of DRDO as technology partner, the Indian Academia (IITs, IIS, NIAS, etc) and other private defence industries to design and develop the FICV. The selected design can be developed and produced by select agency(s) in India. The key would, of course, be evolution of a design capable of being developed, and thus, the interface and ownership of both the design and development agency. The design and development of FICV and the management programme must include an “Empowered Apex Project Management Committee”. This approach must ensure short and quick decision cycles with adequate financial support, oversight measures, flexibility to review and refine at each stage, spiral approach based on mature technologies initially and subsequent development process to incorporate the latest and emerging technologies. The project must visualise and be institutionalised based on a “womb to tomb” concept. The project being on national strategic security importance must not be bound by DPP regulations but shaped by an “Apex Project Management Team,” with responsibility, delegation of authority and accountability dovetailed and clearly defined. This would ensure it to be outcome oriented under an enabling mechanism and broad guidance, with delegated powers to make informed decisions, for timely delivery of the desired FICV.

Alternate Approach 2: Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Model

If India is to attain self-reliance in the defence industry, better infrastructure is needed to build, sustain and improve upon the present capabilities. Public-private partnerships (PPP) could meet this challenge. Private defence manufacturers could use the PPP route to build critical defence equipment like FICV for the country.

The private sector defence firms which evinced interests in the ambitious FICV project included L&T, Tata Motors and Bharat Forge Ltd. According to the original proposal, the FICV were to be manufactured under the ‘Make (high tech) category’ of the Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP). Under this plan, the government was to select state-run Ordnance Factory Board and two other private firms for separately developing prototype of the FICV.

Larsen and Toubro Armoured Systems, recently inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Gujarat, showcased the first glimpses of its Futuristic Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) as a fully indigenously developed Infantry armored fighting vehicle which aims to replace the old BMP-2/2K infantry combat vehicle (ICV) fleet in the Indian Army. Tata Motors led consortium’s Futuristic Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) is aimed at providing a fully indigenous ICV as a replacement to Indian Army’s existing fleet of BMP-2s. Similarly, Bharat Forge is prepared to come out with Future Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV). Rajinder Singh Bhatia, the President and CEO of Defence and Aerospace Division of (Kalyani Group’s) Bharat Forge said, “We are fully prepared to come out with FICV, which will meet all the requirements of the customer and the aspirations of the future of Indian Army”.

Public-private is the principal way in which the private sector through financial investment, talent sharing, management skill transfer, joint ventures and provision of additional resources can join hands, optimising government assets like OFB, wherein infrastructure and experience already exists. Even cost sharing could be based on a mutually agreed arrangement of risk sharing and gain sharing. However, it must be ensured that the levers of comprehensive ToT and IPR rests with Indian firm. In general, PPP model for FICV will provide a strong impetus for technological innovation and outcome oriented arrangement, where in competition and associated negative trends, give away space for hand holding collaboration and cooperation. Implementation of PPP model will thus contribute to the evolution of a domestic ‘techno-industrial’ capability for the production of FICV. PPP arrangements will also offer distinct advantages both to the private sector and DPSU/OFB, leading to win-win situations with mutual benefit for all participants. For the FICV, the partnership model could be OFB as the principle integrator, with active participation in design and development by private defence industry/DPSUs and their JVs, and DRDO as technology partner, all collaborating together. The necessary integration of academia could also be done. The government could play the role of a catalyst. Such a model has several success stories world over. Of course, it entails the risk of putting all your eggs in one basket, and thus, must have a fall back option inbuilt.

Concluding Thoughts

FICV programme must not be allowed to figure in the obituary columns. Indian Army restructuring, particularly the Integrated Battle Groups, mandate matching platform capabilities like the FICV. We need to be a part of the solution and not the problem, to stymie the present status quo. If Make 1, inspite of all the progress and merit, is doomed to be meet its death knell, then other options including a De Novo approach merits consideration.

The author recently retired as Director General, Mechanised Forces, Indian Army.