INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- MoD initiates comprehensive review of Defence Acquisition Procedure 2020, pushes for defence reforms

- G7: The Swansong

- Kalinga Connect: South Asia to Polynesia

- Must Credit DRDO for Operation Sindoor, now what is next for defence R&D?

- The layered Air Defence systems that worked superbly, the key element of Operation Sindoor

- Operation Sindoor | Day 2 DGMOs Briefing

- Operation Sindoor: Resolute yet Restrained

An Overview of 1965 Indo-Pak Conflict Strategic and Operational Insights

Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri wanted to ensure that the world understood that the conflict was started by Pakistan and wanted a ceasefire without conditions

India’s defeat in 1962 encouraged the Pakistani troika comprising Field Marshal Ayub Khan, President of Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the Foreign Minister and General Muhammad Musa the Commander in Chief, to perceive that Indians were not fighters. Field Marshal Ayub Khan had stated that one Pakistani soldier was equal to three Indian soldiers. The troika were convinced that once the new military hardware was received from the United States as members of SEATO and CENTO, and was absorbed by its armed forces, Jammu and Kashmir could be wrested from India. They also appreciated that in addition if an important city like Amritsar were captured by the Pakistani Army, India would have to agree to the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to Pakistan. Moreover Pakistan saw China as an ally who could be counted upon for their devious plans against India.

The Pakistani troika were aware that with modernised armed forces Pakistan was in a militarily strong position to defeat India particularly since India was in a precarious position on the subcontinent with a Chinese threat to the north and Pakistani threats from east and west

From 1954 to 1963, Pakistan received a variety of armament from the US for its army, navy and air force. The army received 650 Patton, M 36B2 Tank Busters, Chaffee and Walker Bulldog tanks, 200 M113 Armoured Protected Carriers (APCs), 105mm and 155mm artillery guns, anti-tank recoilless rifles (RCLs) and Cobra anti-tank missiles and a large quantity of small arms and machine guns of various types. The air force was equipped with two B-57 bomber squadrons, one F-104 supersonic squadron, nine F-86 Sabre jet squadrons, one C-130 transport squadron, six other squadrons of various aircraft, 30 helicopters, Falcon Sidewinder missiles and many types of bombs and rockets. The navy was modernised with one cruiser, five destroyers, eight minesweepers, one water tanker, one submarine and three tugs. All these weapon systems were front line equipment of NATO forces and to ensure interoperability, the Pakistani armed forces were suitably trained.

Following its defeat in Indo-China conflict of 1962, India expanded its defence budget from Rs. 300 crore in 1962 to over Rs. 800 crore in 1965. Most of this defence expenditure went towards raising additional mountain divisions to face a threat from China. It needs to be remembered that the defeat in NEFA in 1962 involved only 4 Infantry Division in the Kameng Division of NEFA and one infantry brigade further east at Walong in the Lohit Division. The Indian Army had given a good account of itself in Ladakh and along the Indo-Tibet border. The major weapon systems of India were mainly those that had been employed during World War II. For the land battle the Pakistani M 47 and M 48 Patton tanks completely outclassed our main battle tank, the Centurion Mk VII, in mobility, firepower and protection, at least in theory. Pakistan Army (GHQ) taking a calculated risk by not keeping any tanks as war wastage reserves, raised eight pure Patton regiments and three mixed regiments in which there was one squadron out of three of M 36B2 Tank destroyers. The M 36B2 had the same gun as the Patton tank and cleverly, the GHQ, had installed the Patton gun on their Sherman Mk II fleet creating four armoured regiments called Tank Delivery Units that were essentially armour available to its infantry divisions. Pakistani Patton tanks, M 36B2 and Sherman II upgunned tanks could destroy any known Indian tank whereas India had only four Centurion Mk VII regiments that could compete against Pakistani armoured regiments. The Pakistani artillery with its new equipment was far superior to Indian artillery both in range and firepower. The firepower with Pakistani infantry was also much greater than that in the Indian infantry unit. In the air, the Pakistani F-104 Starfighter and F-86 Sabre Jet outclassed Indian combat aircraft. Pakistan by modernising its armed forces had achieved technical and organisational superiority and surprise.

Pakistan knew Indian military weaknesses and Bhutto who had visited China assured the President of Pakistan and its Commander in Chief that in the event of a conflict in the subcontinent, China would ensure that India would be unable to move forces from the eastern theatre. However, there was still a need to test the mettle of Indian Army and India’s will before moving on to Kashmir and a wider contest of arms.

Pakistan Launches Operation Desert Hawk in Kutch

On April 9, 1965, Pakistani 51 Infantry Brigade with 24 Cavalry (Patton tanks), crossed the international border in the Kutch area by arrogantly claiming that India was in occupation of Pakistani territory! To the Pakistani higher command, the Indian reaction by its Kilo Sector to the intrusion in Kutch seemed to prove that India was on the defensive. Air Chief Marshal Asghar Khan of Pakistan surprisingly called his counterpart in India, Air Chief Marshal Arjan Singh and suggested that air forces of the two countries should not contribute to the escalation of the situation. Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri was informed about the message from Pakistan and on asking Arjan Singh his views, was told by the Chief of Air Staff that air forces of both countries should not be employed. General J.N. Chaudhuri, Chief of Army Staff, suggested that the Kutch area was not suitable for large scale employment of forces and it would suit India not to escalate the conflict there. If required, India could escalate war at a place of own choosing.

Pakistan by modernising its armed forces had achieved technical and organisational superiority and surprise

Pakistan’s Operation Gibraltar – Infiltration into Jammu and Kashmir

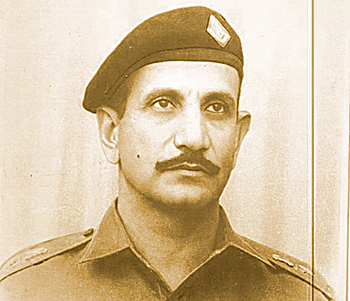

The Kutch operation was actually the first phase of Pakistani strategy while the second phase had already started in tandem. Pakistan believed that there was considerable unrest against India amongst the population in Kashmir and all that was required was a spark to set off a conflagration and Kashmir would fall to Pakistan. A ‘Gibraltar Force’ was raised by Pakistan for infiltration into Kashmir and Major General Akhtar Hussain Malik, General Officer Commanding 12 Infantry Division, a follower of the Ahmadiya Muslim sect, was named commander of this force. On May 26, 1965, four centres were opened in Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK) to train the force in guerrilla operations. The entire force of 30,000 was organised into eight sub-forces with five companies each that had 110 men in a company. Pakistani Army brigadiers commanded each sub-force while its officers commanded companies and Junior Commissioned Officers and Non Commissioned officers provided the stiffening in lower commands. On August 1, 1965, Major General Malik received the ‘go-ahead’ from the GHQ and on August 5, armed infiltrators crossed the ceasefire line (CFL) between Jammu and Kargil into Jammu and Kashmir.

Counter Offensives Planned by the Indian Army

At the start of the conflict in Kutch, the Indian Army had moved to the western border against Pakistan under Operation Ablaze. The army remained in place even after the Indo-Pak agreement of Kutch and plans were made for the different contingencies that might arise if there were a conflict with Pakistan. In April 1965 the Indian Army created a new formation, I Corps, that was to be a strike corps to operate in the plains, a concept new to the subcontinent. I Corps was to carry out swift, flexible and devastating operations into Pakistan however the means to do so were limited. 1 Armoured Division was the only formation capable of carrying out mobile operations whereas India’s infantry divisions that were to be part of this Corps did not have matching mobility. At this stage there were no higher directions of war issued by the government to its armed forces. Thus army and theatre plans emerged as the war objectives were defined by the government. It is only on May 15, 1965, that General J.N. Chaudhuri stated the objectives of XI Corps. These were: to protect Indian territory from Pakistani aggression and occupation, to pose a threat to Lahore by securing the Ichogil Canal and destruction of enemy forces, particularly his newly acquired armour. No part of these objectives called for the capture of Lahore however the destruction of enemy forces was an imperative. The objectives of the new I Corps involved crossing the International Border between the Road Jammu-Sialkot and Basantar River and secure a bridgehead in Area Pagowal (Bhagowal)-Phillora-Cross Roads with a view to advancing towards Marala Ravi Link Canal and eventually to the line of Dhalewali-Wuhilam-Daska-Mandhali. However the destruction of enemy forces remained a constant. The Western Army Commander’s plan for a launch of the I Corps across Ravi River into Pakistan was not accepted and neither was he called for a conference to Army Headquarters when the Chief of Army Staff (COAS) decided the objectives for I Corps. This created a breach between the COAS and the Western Army Commander. This wound continued to fester to the disadvantage of I Corps throughout the war.

Pakistan’s Operation Grand Slam and Indian Reactions

On launching Operation Gibraltar on August 5, Pakistan had hoped for the benefit of surprise but a shepherd in Gulmarg reported strange people in the area and very soon an Indian Army response was set in motion. To the astonishment of Pakistan the peoples of Kashmir did not welcome the infiltrators and rather gave them up to the Indian Army. To stem the influx of infiltrators the Indian Army felt free to also step over the CFL and plug the routes of infiltration. With the capture of the Haji Pir pass on August 29, a link up was effected between Uri and Poonch. It was evident to Pakistan that Operation Gibraltar was a failure and a large number of troops of Gibraltar Force were trapped in Kashmir. Pakistani high command felt the only expedient available was to launch an immediate attack into the Chhamb Sector with the object of capturing Akhnoor and then Jammu and hoping that since the attack was in Jammu and Kashmir, India would react only in that state and not across the International Boundary (IB) elsewhere. Should India react across the IB, Pakistan GHQ had plans for attacks by 6 Armoured Division and 15 Infantry Division towards Jammu, Samba and Sialkot; and 11 Infantry Division and 1 Armoured Division to encircle the city of Amritsar through Khem Karan by capturing Harike and the Beas River Bridge. This was named Operation Grand Slam.

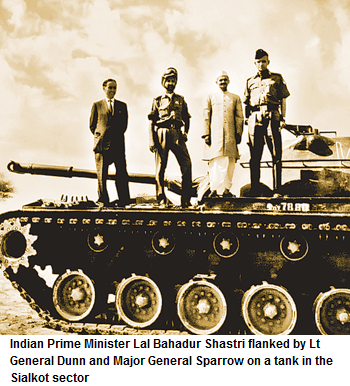

Major General Akhtar Hussain Malik of 12 Infantry Division was given the task of attack in Chhamb Sector in addition to the actions of Gibraltar Force. With troops hastily given to him from 6 Armoured Division and 7 Infantry Division and some from his own division, he attacked across the CFL and parts of the International Boundary, into the Chhamb Sector, on the morning of September 1, 1965. The initiative having been seized by Pakistan, India could only react. The COAS was in Srinagar when the attack was reported to him and he immediately informed the Prime Minister. On landing at Delhi the same afternoon, the COAS went to meet the Prime Minister and requested for the air force to intervene in Chhamb and by 1719 hours the air force went into action there. On September 2, the Prime Minister met the COAS and it was decided that in order to defend Kashmir it was essential to make a diversionary attack on West Pakistan which would force the Pakistanis to give up their venture in Kashmir and defend their own territories. The same evening a conference was held at Army Headquarters chaired by the COAS and attended by Lt General Harbaksh Singh, VrC, the Western Army Commander, Lt General P.O. Dunn, General Officer Commanding I Corps, Major General Rajindar Singh ‘Sparrow,’ MVC and staff officers and a provisional date for the offensive was set for September 4/5, 1965.

On September 3, 1965, the Prime Minister called a meeting with Y.B. Chavan, the Minister of Defence, General J.N. Chaudhuri and Air Chief Marshal Arjan Singh and the following war objectives formulated: to defend against Pakistan’s attempts to grab Kashmir by force and to make it abundantly clear that Pakistan would never be allowed to wrest Kashmir from India; to destroy the offensive power of Pakistan’s armed forces and to occupy only minimum Pakistani territory, necessary to achieve these purposes which would be vacated after a satisfactory conclusion of the war. The Indian Navy was not to take part in the conflict and keep within the 200 mile limit from the Indian coast. The war objectives were a reaction to Pakistani offensive in Chhamb Sector, and were designed to force the Pakistan Army to pull out forces from that sector to meet Indian threats elsewhere. The Pakistani offensive in Chhamb Sector was halted along Fatwal Ridge on September 5, both by narrowing of terrain between the hills and Chenab River; and the dogged defence by 28 Infantry brigade.

Indian Army’s 11 Corps Counteroffensive in Punjab

The strategy in XI Corps Zone was to advance after last light from Ambala, Ferozepur and Amritsar, on axes Amritsar-Dograi-Lahore with 15 Infantry Division, Bhikkiwind-Barki-Lahore with 7 Infantry Division and Khem Karan-Kasur-Lahore with 4 Mountain Division, secure the line of Ichhogil Canal by last light on September 6. 4 Mountain Division was to move the longest distance, into sector predicted to be the sector of the launch of Pakistani offensive but had only six battalions and a mountain artillery brigade that did not have the punch of artillery in other sectors. 7 Infantry Division advanced steadily on the central axis and by 2030 hours on September 10, captured Barki on the Ichhogil Canal. 15 Infantry Division advanced on the northern axis and after an initial success of reaching the Ichhogil Canal with some troops across it on September 6, had to fall back and it was only on September 22 that Dograi was captured and the east bank of the Ichhogil secured. On the southern axis, there was some success towards Kasur on the Rohi Nallah short of the Ichhogil Canal and at Theh Pannuan however a counterattack by 11 Infantry Division of Pakistan forced the division back to the Chima-Assal Uttar area where it went into defence.

The Western Army Commander’s plan for a launch of the I Corps across Ravi River into Pakistan was not accepted and neither was he called for a conference to Army Headquarters when the Chief of Army Staff (COAS) decided the objectives for I Corps. This created a breach between the COA S and the Western Army Commander.

Pakistan 11 Infantry Division and parts of 1 Armoured Division launched a series of attacks on 4 Division and 9 Horse at Chima-Assal Uttar between September 8 and 10. Indian 2 Independent Armoured Brigade arrived in sector by the evening of September 8 and 3 Cavalry equipped with Centurion Mk VII tanks changed the balance of forces in favour of India. In a brilliant offensive-defensive battle by 2 Independent Armoured Brigade, 9 Horse and the pivot of 4 Mountain Division defences at Chima-Assal Uttar, all attacks by Pakistani forces were defeated with a loss of 97 tanks of which most were Patton tanks. With a major victory by Indian 1 Armoured Division at Phillora on September 11 in the Sialkot Sector, Pakistan pulled out 1 Armoured Division from Khem Karan and sent it to Sialkot Sector. Henceforth there was no armour threat to the XI Corps Zone.

Indian Army’s 1 Corps Counteroffensive in Sialkot Sector

I Corps began its advance into the Rachna Doab—the area between the Ravi and Chenab Rivers—on September 8 by when unknown to our formations, the Pakistani 6 Armoured Division had moved into the sector and placed a strong combat command of two Patton regiments and one motorised battalion 45 minutes away from Phillora, the main objective of 1 Armoured Division. 26 Infantry Division of the corps that had been tasked to contain Sialkot successfully established bridgeheads on two axes to Sialkot by the morning of September 8. Two brigades of 6 Mountain Division established bridgeheads for 1 Armoured Division that broke out from one of them at Charwa at first light on September 8. Post monsoon the area was thick with sugarcane, paddy and maize fields and the soil was soft making the ‘going’ for tanks tricky. 16 Cavalry advanced too rapidly and came to a meeting engagement with two Patton squadrons and suffered casualties. 17 (Poona) Horse also contacted a squadron of Patton tanks. The brigade commander decided not to continue frontal attacks that day and the division commander, taking over the battle, felt reconnaissance was essential to make a plan to get to the flank of the enemy and destroy him. Having made a plan, the division commander decided to keep no reserves and attack with three Centurion regiments simultaneously from a flank on September 11, to destroy the enemy and capture Phillora. Although there were two Sherman tank regiments also in the division, they could not be employed in an offensive against Patton tanks. The attack on Phillora was launched on September 11. By 1130 hours 11 Cavalry Patton tanks were decimated; there followed a counter attack by 10 Cavalry (Guides) Patton tanks and this was severely mauled. By 1530 hours Phillora was captured and 51 Patton and M 36B2 tanks had been destroyed. The myth of the superiority of Patton tanks had been shattered by the courage and professionalism of tank crews of 1 Armoured Division. Pakistan now realised that the strategic centre of gravity had shifted to the northern plains of Pakistan with the threat to Sialkot. At this stage there was no credible threat to XI Corps Zone and repeated requests by GOC 1 Armoured Division and GOC 1 Corps for move of additional armour to Sialkot Sector failed to elicit a response by Western Command. By September 23, 1 Armoured Division had destroyed 162 enemy tanks and I Corps had captured 200 square miles of Pakistani territory. Had the Western Command agreed to the move of 2 Independent Armoured Brigade to Sialkot Sector, the progress of Indian offensive could have brought Pakistan to its knees.

Building World Opinion

While the battles were going on the Prime Minister was engaged in building world opinion in the favour of India and accepting a ceasefire only if it suited the war objectives of India. He sent a governmental team headed by M.C. Chagla to the United Nations in New York. Simultaneously he hosted the visit of U. Thant, Secretary General of the United Nations, on September 7. The Prime Minister wanted to ensure that the world understood that the conflict was started by Pakistan by launching first Operation Gibraltar and then Operation Grand Slam. He also wanted a ceasefire without conditions that Pakistan wanted by including a resolution of the Kashmir issue. It was through his patience, intelligence and perseverance that dates to ceasefire kept shifting from September 14 to September 16 and then finally, without pre-conditions, to 2200 hours GMT on September 22 corresponding to 0300 hours on September 23 in India and 0330 hours in Pakistan.

India Administers a Defeat

Historically the Indo-Pak War of 1965 was started by Pakistan on April 9, 1965, Pakistan launched the attack in Kutch to test the mettle of Indian forces. Even while Kutch agreement talks were in process, Pakistan was training 30,000 infiltrators led by personnel from the Pakistani Army to infiltrate into Jammu and Kashmir. On the failure of Operation Gibraltar, Pakistan launched Operation Grand Slam to capture Akhnoor and Jammu. The Prime Minister took an enormous decision fraught by risk, to open a second front in West Pakistan that Lt General Harbaksh Singh later termed, “the biggest decision by the smallest man!” The plan of XI Corps to secure the line of Ichhogil Canal relying only on surprise and without establishing adequate firm bases was faulty, as was the staggered launch of I Corps later on September 8 after strategic surprise was lost. With 4 Mountain Division digging in its heels at Chima-Assal Uttar and 2 Independent Armoured Brigade with 3 Cavalry and 9 Horse executing an armour offensive-defensive battle, 97 tanks of Pakistani 1 Armoured Division were destroyed. The very next day, on September 11, 1 Armoured Division won a classic armour battle of manoeuvre at Phillora that changed the centre of gravity of the whole campaign. With no credible armour threat to XI Corps Zone, the Western Command should have shifted maximum of armour into the Sialkot Sector to secure a strategic victory there.

Considering the war objectives given by the Prime Minister and despite lack of modern weaponry as compared to Pakistan, Jammu and Kashmir remained secure and many sensitive areas captured across the CFL, Pakistani offensive capability was crushed, and minimum territory was captured. Thus all war objectives were met. India and its armed forces had risen to unprovoked aggression by Pakistan and administered a defeat to Pakistani arms.

The author took part in 1965 war as a troop leader of 9 Horse (The Deccan Horse) in the Khem Karan Sector. He with Amarinder Singh, the former Chief Minister of Punjab, have written a book on 1965 war which is to be released on September 20, 2015.